Previous Posts

If you’ve ever done any sort of repeated measures analysis or mixed models, you’ve probably heard of the unstructured covariance matrix. They can be extremely useful, but they can also blow up a model if not used appropriately. In this article I will investigate some situations when they work well and some when they don’t […]

How to do it In stratified sampling, the population is divided into different sub-groups or strata, and then the subjects are randomly selected from each of the strata. So, in the above example, you would divide the population into different linguistic sub-groups (one of which is Yiddish speakers). Here are two simple steps you should follow:

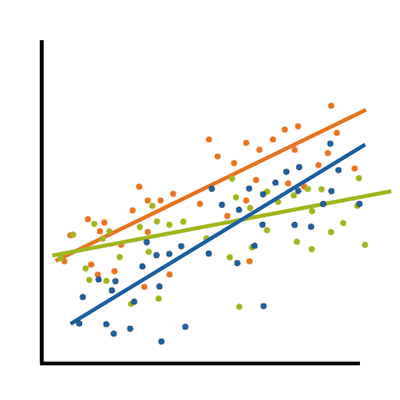

What that means is there is no way to express in one number how X affects Y in terms of probability. The effect of X on the probability of Y has different values depending on the value of X.

The assumptions are exactly the same for ANOVA and regression models. The normality assumption is that residuals follow a normal distribution. You usually see it like this: ε~ i.i.d. N(0, σ²) But what it's really getting at is the distribution of Y|X.

R² is such a lovely statistic, isn't it? Unlike so many of the others, it makes sense--the percentage of variance in Y accounted for by a model. I mean, you can actually understand that. So can your grandmother. And the clinical audience you're writing the report for. A big R² is always big (and good!) and a small one is always small (and bad!), right? Well, maybe.

But there are many design issues that affect power in a study that go way beyond a z-test. Like: repeated measures clustering of individuals blocking including covariates in a model Regular sample size software can accommodate some of these issues, but not all. And there is just something wonderful about finding a tool that does just what you need it to. Especially when it's free.

Factor is tricky much in the same way as hierarchical and beta, because it too has different meanings in different contexts. Factor might be a little worse, though, because its meanings are related. In both meanings, a factor is a variable. But a factor has a completely different meaning and implications for use in two different contexts. Factor analysis In factor analysis, a factor is an unmeasured, latent variable, that expresses itself through its relationship with other measured variables.

Generalized linear models, linear mixed models, generalized linear mixed models, marginal models, GEE models. You’ve probably heard of more than one of them and you’ve probably also heard that each one is an extension of our old friend, the general linear model. This is true, and they extend our old friend in different ways, particularly in regard to the measurement level of the dependent variable and the independence of the measurements. So while the names are similar (and confusing), the distinctions are important.

You may have noticed conflicting advice about whether to leave insignificant effects in a model or take them out in order to simplify the model. One effect of leaving in insignificant predictors is on p-values–they use up precious df in small samples. But if your sample isn’t small, the effect is negligible. The bigger effect […]

Interaction is different. Whether two variables are associated says nothing about whether they interact in their effect on a third variable. Likewise, if two variables interact, they may or may not be associated.

stat skill-building compass

stat skill-building compass