Previous Posts

You can see that indeed, all the coefficients (Estimate column) are identical, but with opposite signs. Except the intercepts, which are identical. Mystery Solved As it turns out, SPSS and Stata did something clever. SAS and Minitab parameterize the model in the usual way—the same way any regression model does:

There are dozens of measures of association. Even just correlations come in many flavors: Pearson, Spearman, biserial, tetrachoric, squared multiple, to name a few. And there are many measures beyond correlation.

One great thing about logistic regression, at least for those of us who are trying to learn how to use it, is that the predictor variables work exactly the same way as they do in linear regression. Dummy coding, interactions, quadratic terms--they all work the same way.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is a handy statistical tool to always have available in your data analysis tool belt. It's a data reduction technique, which means it's a way of capturing the variance in many variables in a smaller, easier-to-work-with set of variables. There are many, many details involved, though, so here are a few things to remember as you run your PCA.

MANOVA is the multivariate (meaning multiple dependent variables) version of ANOVA, but there are many misconceptions about it. In this webinar, you’ll learn: When to use MANOVA and when you’d be better off using individual ANOVAs How to follow up the overall MANOVA results to interpret What those strange statistics mean — Wilk’s lambda, Roy’s Greatest Root (hint — it’s not a carrot) Its relationship to discriminant analysis

In Part 3 ans Part 4 we used the lm() command to perform least squares regressions. We saw how to check for non-linearity in our data by fitting polynomial models and checking whether they fit the data better than a linear model. Now let’s see how to fit an exponential model in R.

One important consideration in choosing a missing data approach is the missing data mechanism—different approaches have different assumptions about the mechanism. Each of the three mechanisms describes one possible relationship between the propensity of data to be missing and values of the data, both missing and observed.

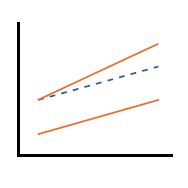

Graphing predicted values from a regression model or means from an ANOVA makes interpretation of results much easier. Every statistical software will graph predicted values for you. But the more complicated your model, the harder it can be to get the graph you want in the format you want. Excel isn’t all that useful for estimating the statistics, but it has some very nice features that are useful for doing data analysis, one of which is graphing.

In all linear regression models, the intercept has the same definition: the mean of the response, Y, when all predictors, all X = 0.

We will use a data set of counts (atomic disintegration events that take place within a radiation source), taken with a Geiger counter at a nuclear plant. The counts were registered over a 30 second period for a short-lived, man-made radioactive compound. We read in the data and subtract the background count of 623.4 counts per second in order to obtain the counts that pertain to the radio-active source. Cut and paste the following data into your R workspace.

stat skill-building compass

stat skill-building compass