One of the many decisions you have to make when model building is which form each predictor variable should take. One specific version of this decision is whether to combine categories of a categorical predictor.

decision is whether to combine categories of a categorical predictor.

The greater the number of parameter estimates in a model the greater the number of observations that are needed to keep power constant. The parameter estimates in a linear regression model are the coefficients of the predictors.

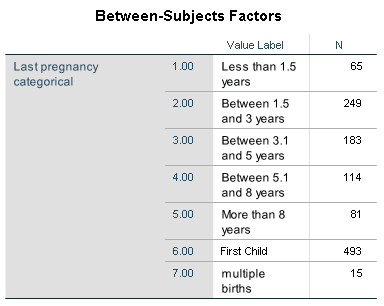

Every continuous predictor has one parameter estimate (one regression coefficient). A categorical variable has one fewer than the number of categories of the categorical predictor. Here is a categorical predictor for the number of months since a mother’s last pregnancy.

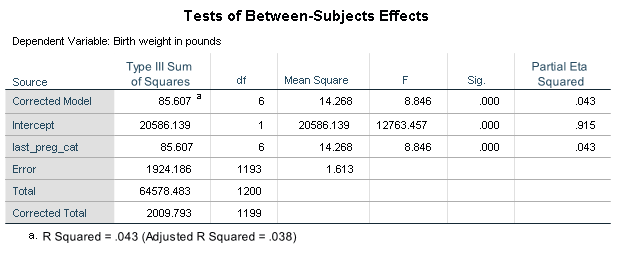

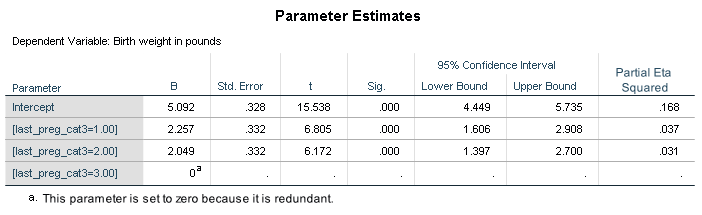

Regressing a baby’s birth weight on this predictor produces the following results.

There are six parameter estimates in this model. Remember, more estimates lowers the power of our model.

Do we need seven categories to represent the number of months since the last pregnancy? Remember, the coefficient of a category is the comparison of its birth weight to the birth weight of the base category (reference group). In this model the base category is multiple births.

Multiple births tend to have very low birth weights. The coefficients for the non-multiple birth categories are in the range of 2.01 to 2.34 pounds greater than multiple births. If we used a different category as our base we would most likely have fewer estimates with such low p-values. Please note the main effect of months since last pregnancy as shown in the table “Tests of Between-Subject Effects” would not be affected.

Perhaps we don’t need seven categories. Running a pairwise comparison can help us determine whether two categories are different. If categories are not statistically different then it might be possible to combine them.

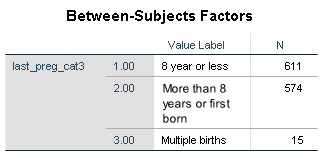

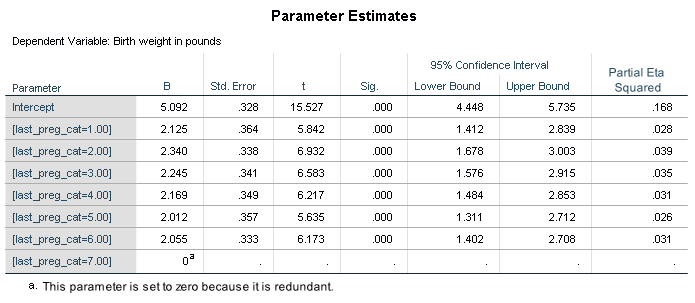

After running the pairwise comparison tests, it was determined that all previous pregnancies within the past eight years could be combined into one category. First born and last pregnancies of more than eight years ago were combined. Multiple births remained in their own category. The categorical predictor now has only three categories.

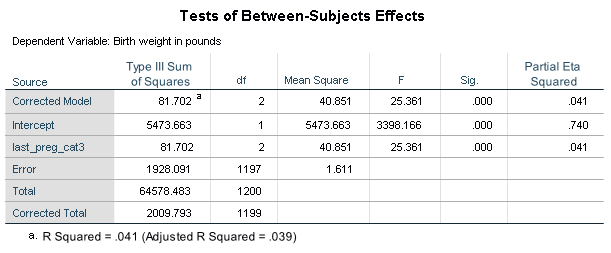

Below are the results of the model using the categorical variable with three categories.

The adjusted R square is higher in the new model with only two parameter estimates. An added bonus, the more parsimonious model will require less written explanation for the final analysis.

One more step is required before deciding which categorical variable to use. Does the new combination of categories make theoretical sense? Data shows birth weight of multiple birth babies is less than single births. Research has shown that first born babies have lower birth weight than second born babies. What does research show about birth weights when the time between pregnancy is 8 years or more? Researchers should always be aware of the hypothesized population and not fit their models to their sample.

It’s also important to be transparent in these decisions. If you do combine similar categories with similar effects in order to tell a more parsimonious story, make that clear to your reader.

In this example, the decision to choose the smaller categorical variable should not be driven by the slight improvement in the adjusted R-square. The increase is minimal. However, the more parsimonious model will require less written explanation. If the variable is not a key predictor of the analysis this is advantageous.

Jeff Meyer is a statistical consultant with The Analysis Factor, a stats mentor for Statistically Speaking membership, and a workshop instructor. Read more about Jeff here.

Leave a Reply